Software Model is a constant conversation with domain experts and with code.

DDD fundamentally centers around the model as the key to bridging the gap between a real-world problem and its software solution. In DDD, the model isn’t just a blueprint; it plays a crucial and active role throughout the entire design and development process. Crucially, we model the problem, not just the solution.

We model the problem, not just the solution.

From my perspective, this model serves as a shared understanding, crafted in a way that resonates with all stakeholders involved in building the software , the business experts who define the domain, the product owners who shape the requirements, and the software engineers who bring it to life. Ideally, this model should also be readily translatable into software code, perhaps through informal notations akin to a flexible UML, allowing for a smoother transition from concept to implementation.

This model isn’t a static, top-down creation, finalized in the initial stages. Instead, it’s more of a Just-In-Time artifact, emerging and evolving as the conversation between the development team and domain experts progresses. This constant dialogue fuels the model’s growth and refinement.

A model is more of a Just-In-Time artifact emerging and evolving as the conversation between the development team and domain experts progresses.

Furthermore, a constant dialogue between the development team and the code itself is equally vital. As the software takes shape, the code can reveal insights and complexities that might not have been apparent initially. This ongoing interaction necessitates reflecting these discoveries back into the model. Ultimately, the model’s core responsibility is: to bridge the gap between the problem space and the solution space, striving for a clear, one-to-one relationship between the concepts in the problem domain and their corresponding representations in the software.

A constant dialogue between the development team and the code itself is equally vital.

At its heart, Software Design is a Constant Dialogue between Language and Model. The clarity and precision of our language shape the abstract representations within the model, and conversely, the evolving model demands more specific and nuanced language to accurately capture its intricacies. Each design decision and iteration is a turn in this ongoing exchange, ensuring the design truly reflects the intended functionality and structure.

At its heart, Software Design is a Constant Dialogue between Language and Model.

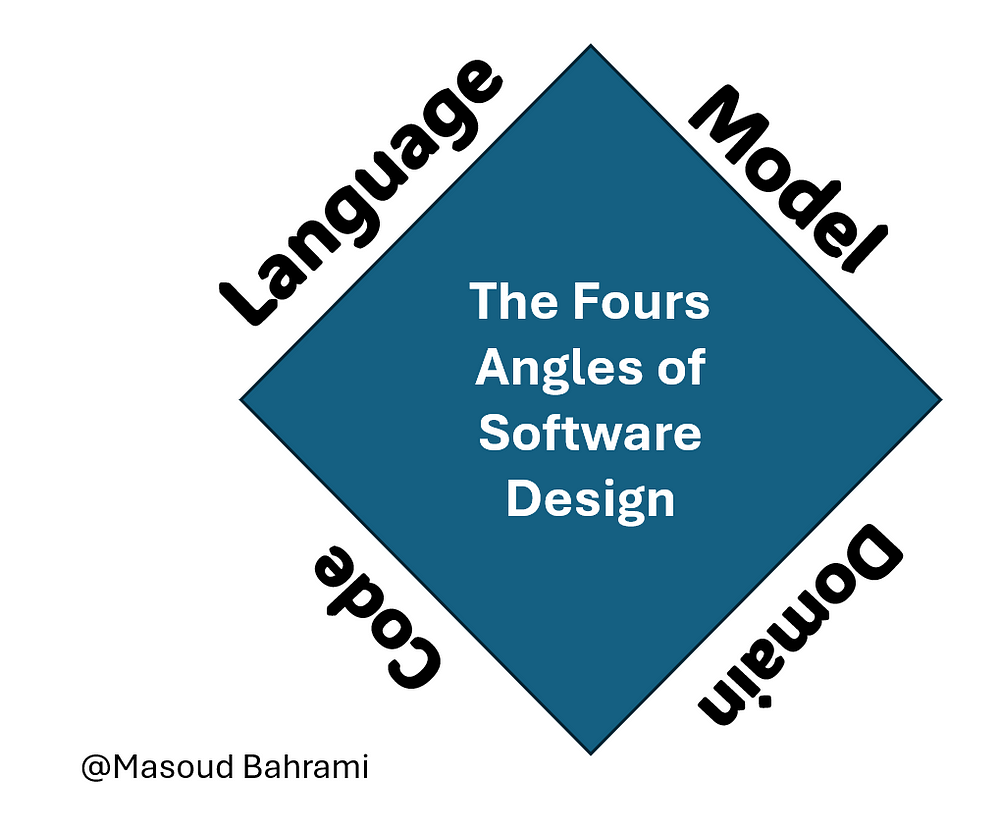

But this dialogue doesn’t occur in isolation. The Software Model is a constant conversation with domain experts and with code. It must faithfully represent the real-world processes and entities understood by domain experts, translating their knowledge into a structured framework. Simultaneously, it must speak the language of code, providing a practical and implementable foundation for the developers. This dual conversation ensures that the software not only solves the right problem but does so in an efficient and maintainable way. We can think of these crucial elements , Language, Model, Domain Experts, and Code , as the Four Angles of Software Design, each offering a vital perspective that shapes the final outcome.

The Essential Angle: Dialogue with Domain Experts

Imagine trying to build a tool for doctors without ever speaking to one. You might create something technically impressive, but it could completely miss the mark in terms of how doctors actually work, the terms they use, and the challenges they face daily. This is why the dialogue with domain experts is an essential angle.

These experts , the people who live and breathe the problem we’re trying to solve, hold a wealth of knowledge that is often nuanced and specific. Our software model, that crucial blueprint we discussed, needs to be built upon this understanding. This isn’t about simply taking their requirements as a list; it’s about engaging in a continuous conversation to truly grasp the underlying concepts, the relationships between different parts of the domain, and the unspoken rules and assumptions that govern their world.

- Uncovering the Real Needs: Through dialogue, we can move beyond surface-level requests to uncover the real needs and pain points. Experts can explain why things are done a certain way, revealing complexities we might otherwise miss.

- Building a Shared Language: This conversation is also about establishing a shared vocabulary. The terms used by domain experts should ideally be reflected in our software model and even in our code. This “ubiquitous language” ensures that everyone on the team, including the experts, can understand and contribute to the design.

- Emerging Understanding: The model isn’t a static thing we create in isolation and then present to the experts. Instead, it emerges from these discussions. As we talk, ask questions, and they explain their processes, our understanding grows, and the model takes shape. It’s a collaborative process of discovery.

Example: For our library software, talking to librarians isn’t just about asking “What features do you need?” It’s about understanding how they categorize books, how they handle different types of loans, what the process for placing a hold looks like from their perspective, and how they deal with overdue items. This deep dive into their daily work informs a much richer and more accurate software model.

The Silent Angle: Dialogue with the Code Itself

The other crucial angle is the dialogue with the code itself. Once we start translating our model into a working system, the code becomes a powerful source of feedback. It can reveal complexities we didn’t anticipate in our initial model or highlight areas where our understanding was incomplete or even wrong.

- Uncovering Implementation Challenges: Sometimes, a concept that seems straightforward in our model turns out to be surprisingly difficult or inefficient to implement in code. This “friction” forces us to revisit our model and potentially simplify or restructure it.

- Revealing Hidden Assumptions: As we code, we might realize that our model made certain assumptions that aren’t actually true in all cases. The code can expose these hidden assumptions and prompt us to refine our model to be more accurate and robust.

- Guiding Model Evolution: The code can also suggest better ways to organize our model. We might find that certain concepts naturally group together in the code, indicating a potential relationship that wasn’t explicitly captured in our initial model. This can lead to a more cohesive and maintainable design.

- Yesterday’s Solution, Today’s Problem: As software evolves, code written in the past can become a constraint or even a source of complexity for new features. Having a “conversation” with this existing codebase helps us understand its limitations and how our model needs to adapt to integrate new functionality effectively.

Example: In our library software, we might have initially modeled “Book Availability” as a simple boolean (available/unavailable). However, as we start coding the borrowing and returning logic, we realize we need to track where a book is (on the shelf, checked out, on hold, in repair) and potentially who has it. The code forces us to make our model of “Book Availability” more detailed and nuanced.

The Iterative Pulse of Model Refinement

It’s vital to recognize that the model is not a static end-product but rather a dynamic entity that evolves over time. The initial model, born from early conversations, is rarely perfect. As the project progresses, as we gain deeper insights into the domain and the practicalities of implementation, our understanding invariably shifts. This necessitates a continuous process of model refinement.

This refinement isn’t a wholesale rewrite but rather a series of adjustments, clarifications, and sometimes even fundamental reconsiderations driven by ongoing dialogue. New features might expose previously unseen complexities in the domain. Interactions with the code might reveal elegant simplifications or necessary adjustments to our initial conceptualization.

The Power of Feedback Loops

Central to this iterative refinement is the importance of feedback loops. The conversation with domain experts doesn’t end after the initial modeling sessions. Presenting them with working software, even in its early stages, provides invaluable feedback. Do the software’s behaviors align with their understanding of the domain? Are the terms and concepts used within the application consistent with their language? These interactions can highlight discrepancies and areas where the model needs adjustment.

Similarly, the code itself provides a crucial feedback loop. Is the model easily translatable into maintainable and efficient code? Are there areas where the model leads to unnecessary complexity or hinders implementation? These technical considerations must also inform the evolution of the model.

By actively seeking and responding to feedback from both the domain experts and the code, we ensure that the model remains a faithful and practical representation of the problem and a solid foundation for its solution.

Ultimately, the strength and resilience of a software system depends on the quality of these ongoing dialogues. A clear and consistent language fosters a robust and understandable model, while a model that effectively bridges the gap between domain knowledge and code paves the way for successful implementation and evolution. It’s in this continuous interplay, this constant conversation viewed from the Four Angles of Software Design,Language, Model, Domain Experts, and Code that elegant and effective software architectures are born. The model, therefore, isn’t just a design artifact; it’s the very foundation upon which effective and insightful software is built.

Leave a Reply